Art & Politics

Various art forms : Kathe Kollwitz (1867-1945) - dealing with poverty, hunger, suffering, death and the tragedy of wars

She embraced the victims and never glorified the powerful or victorious. This is the exact opposite of what many of her contemporary artists were doing. Her art was like a constant thread woven closely into the political, social and economic history of her society and her world, with epic implications and with enduring value to humanity. Can you think of any artists today who are doing something comparable ? Red Line Art Works is keen to draw attention to their work.

She expressed her viewpoint through drawing, etching, lithography, woodcut and sculpture over the course of a long career. At sixteen she began making drawings of working people, the sailors and peasants she saw in her father's offices. In 1891 she married a doctor (Karl Kollwitz) who tended to the people in a very poor area of Berlin, where they lived. From about 1871 (when Berlin became the capital of a united Germany) to 1900 there was rapid population growth, from around 800,000 to 1.9 million. Street after street of tenements were built where living conditions were dire.

Their apartment was their home for over 50 years. Daily contacts with Karl’s patients kept her in close touch with the lives of the people around them - lives beset by the uncertainties of casual employment, poverty and deprivation, high maternal and child mortality, and often domestic violence. Over the next 50 years – through all the horrors the world was to bring - she produced dramatic work expressing deep emotions and clear political observations, which are still relevant today.

In 1913 she co-founded The Organisation of Women Artists which protested that 600,000 Berliners lived in dwellings with five or more people per room while 100,000 children had nowhere to play. It was called ‘the largest tenement city in the world’.

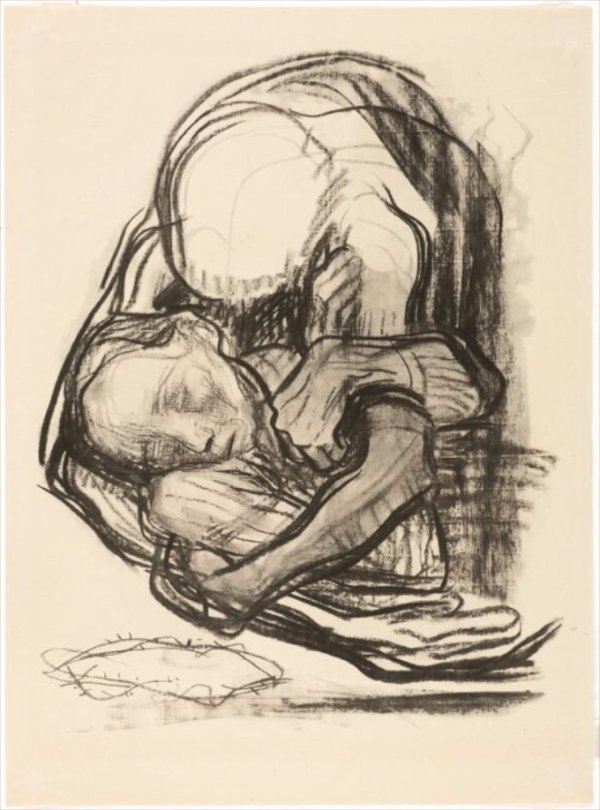

Poverty (1897)

In her second graphic cycle (created from 1902-7) ‘The Peasants’ War’ she used the religious and economic conflict of 1524-5 as a vehicle through which to express the heroism of the working class in her own era. She saw the potential of the print for social commentary. Prints could be reproduced inexpensively and in multiples, allowing her to reach more people. The artistry and technical competence of this series earned her great recognition and propelled her to the front rank of artists in Germany.

Throughout her career she also created numerous very impressive self-portraits. These exude life-force and quiet self-confidence and are a lifelong, honest self-appraisal. In her own words : "They are psychological milestones". As with Rembrandt’s great series of self-portraits, Kollwitz’s exude a deep humility and humanity, looking out at us across time, witnessing humanity, just as we might witness it today.

Kollwitz’s subject matter also came to reflect her experience as a witness to both World Wars. She was devastated by the suffering and loss of human life, including the loss of a son in the first war and a grandson in the second.

She was a committed socialist and pacifist - a very risky and courageous standpoint for anyone living in Germany at the time. As the Nazi regime grew into a fascist totalitarian state her work generated a reaction from the Nazis. You may recall that the Nazis introduced a whole program of banning and destroying whatever it defined as ‘degenerate art’, persecuting and often murdering artists, intellectuals and thinkers.

In 1933, the Nazi government forced her to resign her position as the first female professor appointed to the Prussian Academy (in 1919). Her work was removed from museums and she was banned from exhibiting, although one of her "mother and child" pieces was used by the Nazis for propaganda.

In July 1936, she and her husband were visited by the Gestapo, who threatened her with arrest and deportation to a Nazi concentration camp. Kathe and Karl resolved to commit suicide if such a prospect became inevitable. However, Kollwitz was by now a figure of international note, and no further action was taken against her. In 1937 on her seventieth birthday, she received over one hundred and fifty telegrams from leading personalities of the art world, as well as offers to house her in the United States, which she declined for fear of provoking reprisals against her family.

During her final years her husband died (in 1940) but she went on producing bronze and stone sculpture embodying the same types of subjects and aesthetic values as her work in two dimensions. In 1943 her house was bombed in a Berlin air raid and much of her work was lost. Kollwitz was evacuated to Moritzburg, a town just outside Dresden, where she died two years later in April 1945, just before the end of the war.

Revolt (1897)

The End (1897)

The March of the Weavers in Berlin (1897)

Dance Around the Guillotine (1901)

Woman With Dead Child (1903)

Death Grasps at Children (1905)

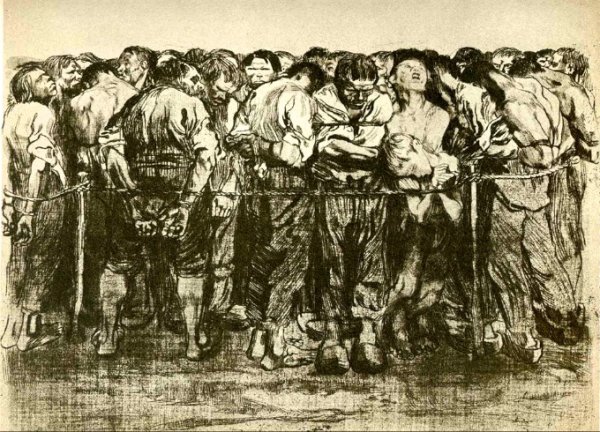

The Prisoners (1908)

Outbreak (1908)

Unemployment (1909)

The Widow (1921)

Killed In Action (1921)

The Mothers (1922)

The Sacrifice (1922)

Hunger (1923)

The Survivors (1923)

Bread ! (1924)

Germany's Children Starve ! (1924)

Never Again War (1924)

Hospital Visit

Solidarity (1932)

Lament (1938-40)

The Grieving Parents

Berlin Neue Wache, Interior View